Jean Charlot's Nativity at the Ranch. John Charlot. February 2020. The Jean Charlot Foundation (jeancharlot.org).

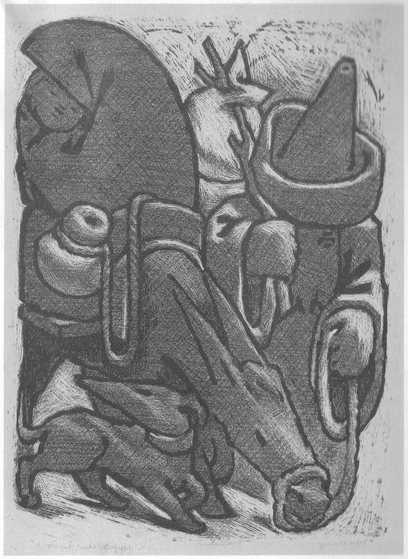

Nativity at the Ranch. Jean Charlot. Fresco. 4 ft × 5 ft. August 26–27, 1953. Chapel at Kahuā Ranch, Kohala, Kamuela, Hawaiʻi.

Ranch chapel.

Jean Charlot's Nativity at the Ranch is a compact statement of his personal connection to a form of modern Hawaiian culture and of his view of Hawaiian religion.[1] Charlot had started his study of Hawaiian culture when he arrived in 1949 and shortly thereafter began studying Hawaiian language and literature. The small fresco mural was commissioned for the ranch chapel by Joseph Atherton Richards (1894−1974) as a memorial to the recently deceased Ronald von Holt (d. February 15, 1952), ranch manager of Kahuā Ranch Limited in the Kohala district of the Big Island of Hawaiʻi.[2]

A business and community leader, Richards had a strong interest in art. He was head of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company, later Dole, when it commissioned Georgia O'Keefe to create two paintings of her own design to be used in national advertisements (Saville 2012: 83, 123). Charles T. Coiner, the art director of the advertising firm, "credited Richards with being a client who appreciated art and was open to using fine art in company advertising" (Saville 2012: 122, note 5). Georgia O'Keefe wrote in February 1939:

I must say that I think Mr. Richards is quite the most interesting person about. He drove me back in an open car—is very much the artist in the surface of him that meets you—A rare sort of person I think. The people that came to the party were really very nice but I must say again I think Mr. Richards the prize of the community so far… (Saville 2012: 91)

Art was an option for Richards when a memorial for von Holt was discussed.

Honolulu society parties were very mixed in the 1950s, including businessmen, politicians, artists, teachers, dancers, and so on. Lawyers were violists in the city orchestra. All sorts played roles in the community theater. My parents met Richards and his wife Helen at such parties, and he himself joined in parties at our little cottage in the faculty housing of the University of Hawaiʻi. My father was impressed when he arrived dressed in his Hawaiian cowboy regalia of white shirt and pants, a magnificent plaited hat, and a broad red sash with hanging end for a belt. Charlot admired Richards' cowboy-style jeep driving and maintenance of local cowboy ways. As a trustee of the Bishop Estate, Richards later helped the Charlots to lease a lot when the Kāhala subdivision was opened.

Richards invited Charlot to visit the Kohala site of the proposed mural, a district with a special cultural history. Charlot wrote in his diary[3] for August 7, 1953:

7:45 AM. Atherton for me. To airport: to ʻUpolu, Hawaiʻi. Sugar country, cattle country—cowboys. See chapel for memorial painting of von Holt. Return by Kona, 2:25 PM.

The chapel was historic, originally built in the 1840s by the famous missionary and song writer Lorenzo Lyons in Kawaihae Uka and fallen into disrepair. Von Holt had brought the chapel to the ranch along with a second one. He was restoring and combining them to serve the staff, when he died unexpectedly. His own funeral would inaugurate the chapel's new use (Melrose 1998).

During Charlot's stay at the ranch, Richards was intent on showing him and his family the magnificent Kohala mountain country, 3200 feet above sea level, driving us in a jeep up the immense, inland valleys of the spread.[4] The district was a historic source of pride for its inhabitants, the men known as warriors and the women as resourceful.[5] Kamehameha had trained his army there, an event that inspired the famous chant Hole Waimea (Elbert and Mahoe 1970: 52 f.). Richards would invite experts from the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum to catalog artifacts found on the property.

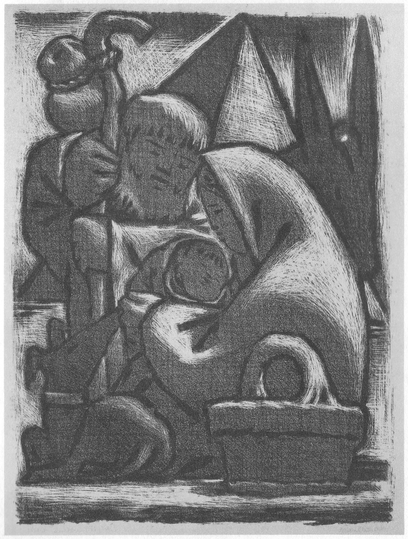

Besides its pre-contact fame, Kohala was home to one of the most successful fusions of Western and Hawaiian culture. Mexican cowboys or vaqueros had been brought to Hawaiʻi in 1832 to teach herding to Hawaiians. Paniolo, the Hawaiian word for cowboy, is based on espagnol, Spanish for Spaniard or the Spanish language. As Hawaiʻi received Western influences throughout the nineteenth century, traditional roles had to be modified or abandoned. Some Hawaiians were born out of their time into roles that had no clear place in their new society (John Charlot 2005: 395). The vaquero role—like others including political leaders, teachers, military, firemen, police, and life guards—was attractive to Hawaiian men, and they adapted it with a success that made them famous prize-winners at rodeo competitions on the mainland United States. The new culture spread into other areas of life. Mexican musical instruments and songs influenced Hawaiian as seen in Adios ke Aloha (Elbert and Mahoe 1970: 28), and such music inspired new dances like Kāula ʻIli. The culture was being passed down to the next generations as represented by the young boy in the fresco, a regular device of Charlot's communication.[6] Charlot celebrated this Hawaiian-vaquero culture—one of Hawaiʻi's most successful syncretisms—on the right side of the mural.

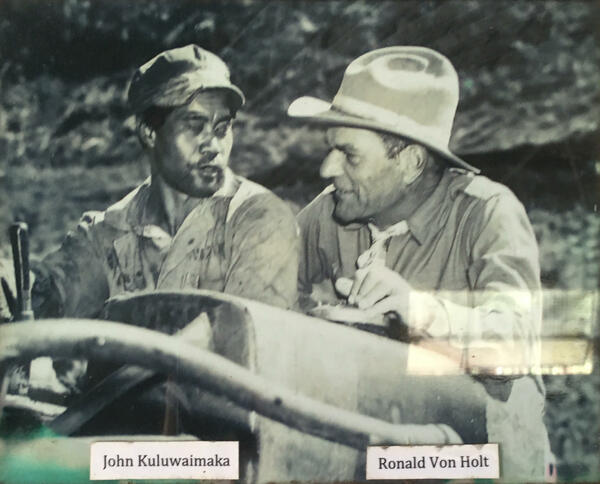

Photo of von Holt that resembles fresco.

A problem Charlot faced with this section was the portrait of Ronald von Holt. Diary August 22 (Started portrait von Holt from photos and hearsay. difficult); also August 23. At the time, Helen Richards, Atherton's wife, showed me one of the photographs Charlot had used—an example of the flattering soft focus favored by business leaders of the time—and I could not imagine how he had reached his own portrayal from that evidence. She told me also that people who knew Holt were astonished at how well my father had caught the subject. One woman, a friend of Holt, burst into tears on seeing it. In 2016, I saw a photograph of Holt that was close to the fresco portrait, but it was not one I was told Charlot saw at the time.[7]

Important for the authenticity of this section was the use of actual Kahuā ranch hands as models.[8] Prominent among these was the ranch foreman, John Iokepa, who lived with his family in the area where the chapel was originally located.[9] Monty Richards, Atherton's nephew, told me that my father considered his portrait of Iokepa the best he had ever done for a fresco. Iokepa himself answered only with an embarrassed smile when asked what he thought of it himself. Ida Lincoln, the Japanese-American ranch cook, was the model for Mary and the mother of Butchie, the boy in the right hand section (Diary August 21, 23, 28). The adult prize bull, I remember being told, had been purchased recently to improve the stock. The figures of Joseph and Jesus are, in my opinion, without models. Charlot's technical assistant and mason was Jim Lincoln, the ranch mechanic.[10] Charlot gave drawings as tokens of thanks to his models and helpers.[11]

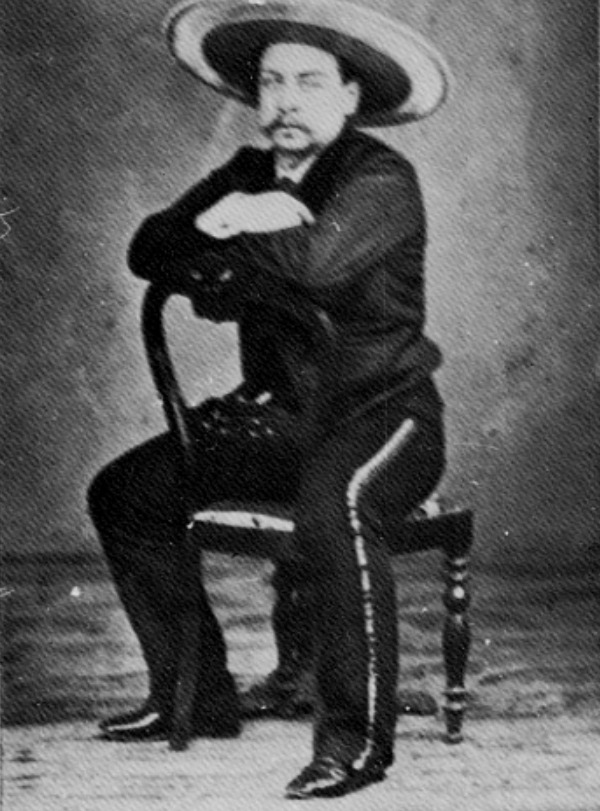

Luis Goupil

Charlot knew the vaquero culture well. He himself was connected to this culture through his grandfather, Luis Goupil, a Mexican vaquero famous in the mid-nineteenth century. He was known for his feat of throwing a bull by chasing it on horseback, grabbing its tail, and holding it between his thigh and the side of the horse until he stopped suddenly and jerked the bull down to the ground. In his old age, he would chase the young Charlot and his sister around their Paris apartment with a lasso. Charlot and his family regularly rode horses when he was young, and he served in the French horse artillery during World War I. These were the kind of adventurous Mexicans who came to Hawaiʻi and helped create a distinctive way of life. Charlot learned of this intercultural connection on January 22, 1951:

tips on Haw cattle Vancouver[12]

: California long horns, from Mexico!

Religion is basic and all-pervasive in both Hawaiian and Mexican culture: their ways of living and world views. Indeed, religion is essential to both peoples' identity. Neither can synthesize a life-style without including religion. But that synthesis, for both Mexicans and Hawaiians, involves a major question: what is the relationship of the traditional religion to the introduced Christianity? This question had to be addressed by the mural as well: how does a Christian chapel and image fit into this Hawaiian place?

Charlot devoted the left side of the mural to this religious question, which had been raised by the depiction of the Hawaiian-vaquero culture on the right side. The post of the hut is placed on the part of the rectangular shape called the Golden Section. This makes the left side a little larger than the right. The three figures on the right are pressed together whereas the Holy Family on the left has more room. The left side is also on a smaller scale so the hut and figures resemble a crèche or shrine such as those found in many homes at Christmas time. Finally, the left figures are more simplified and geometric. This contrast with the comparatively realistic figures on the right makes the left figures appear more ideal, more spiritual.

Our Lady of Guadalupe

The left side of the mural is a proposed mixture of Hawaiian and Christian—or more particularly Mexican-Christian—religious cultures as represented by a background portrait of the chapel itself. The clue to Charlot's message is the figure of Mary. Roman Catholics have different devotions to Mary, and these can be connected to an apparition story. When a particular apparition is depicted in a painting or statue, Mary is shown wearing the clothes described by the people who saw it. For instance, Mary of the Immaculate Conception is dressed in a white robe with blue trim. Unusually for a modern depiction, in Charlot's Nativity, Mary is shown wearing a red cloak over a blue dress. Mexicans would immediately recognize the reference to Our Lady of Guadalupe. Charlot was interested in that apparition—in part because of its connection to an image—and collected Náhuatl texts about it in view of publishing an anthology. Moreover, throughout his life, Charlot depicted that figure, for example, in his mural Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Four Apparitions (1959), his illustrations for Helen Rand Parish's Our Lady of Guadalupe (1955), and in two ceramic statues in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Madonna and Child of 1959 at St. Francis Hospital, and Mary Our Mother of 1978−1979 at Maryknoll Grade School.[13]

Our Lady of Guadalupe. 1955.

Madonna and Child. 1959.

Mary Our Mother. 1978–1979.

The Guadalupe story takes place in 1531, just ten years after the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, a time of great religious and thus cultural confusion. The people were being missionized, which included demonizing their old religion. The polytheistic Indians were happy to have more religious options but still felt strongly connected to their old religion for their world view and practices. Old and new seemed locked in opposition, including religion, history, daily life, morale, self-image, and identity.

The Guadalupe story begins with an Indian peasant, Juan Diego, walking past Tepeyac, a hill near Mexico City. Tepeyac had been the site of a major temple to the Goddess Tonantzin ('Our honored mother'), an earth goddess and the mother of all the human beings. Her temple had been destroyed by the Spaniards, and a little Christian chapel had been built on the site. As Juan Diego was walking beside the hill, he was addressed by a young woman in Náhuatl, the language of the Indians, who said she wanted him to tell the archbishop, Juan de Zumárraga, to build a great church for her on Tepeyac. The story works through the complications of a peasant meeting an archbishop and the cleric's reactions to the request. The archbishop finally asked for a sign, and Juan Diego tried to avoid the task. Finally, he was taking a side road to avoid meeting the lady, but she surprised him on his way. When he made excuses, she asked, "Am I not here who am your mother?" She was identifying herself as the mother of the people, an identification Charlot used in his title of the Maryknoll sculpture, Mary Our Mother. She then instructed him to climb to the top of Tepeyac and gather flowers. This was odd because it was a barren spot and the middle of winter, but when Juan Diego reached the top of the hill, he found Castilian roses, a Spanish, not a Mexican flower. The lady then put the roses in Juan Diego's tilma, a cloak made of leaves that poor people wore. When Juan Diego opened his cloak in front of the archbishop, the flowers fell out, and on the cloak was an image of the lady Juan Diego had been meeting. This was received as the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and the church built to house it has become one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in the world.[14]

Marian apparitions usually communicate a special message or address a certain problem. In Mexico, Our Lady of Guadalupe came to be understood as belonging especially to the people, that is, the natives, the Indians. Her skin is brown, so she is racially Indian. She is dressed as an Aztec princess. She is wearing emblems of the traditional religion: the color blue is connected to the godly male and female couple that represent the origin of the universe. Her black belt shows that she is pregnant. The Indians immediately started calling her Tonantzin "Our honored mother."

Some missionaries were shocked that the name of the Aztec goddess was being applied to Mary. They objected that Mary should be called the mother of Jesus or the mother of God, but not our mother. But the Indians felt they knew better. The image was communicating to them the special message that they could go on being Aztec even when they joined the new religion. They could be both Aztec and Christian. Their old religion was not all evil but could be an important part of their new one. They could be Aztec Christians.

Charlot was extending this message to Hawaiʻi. Mary's skin is brown like the Guadalupe figure. But Charlot was also adapting the image to Hawaiʻi. Our Lady of Guadalupe has a blue outer cloak and inner red robe, the attire of an Aztec princess. Charlot changes this to an inner blue robe and an outer red cloak. The reason is that a Hawaiian aliʻi (noble) would wear a red feather cloak. Blue was not used for symbolic purposes in chiefly regalia (although it was in literature), so Charlot almost hid it, leaving only the top of Mary's blue robe at her neck. His purpose was to make Mary look Hawaiian.

Charlot was an inclusive, not an exclusive, Christian. Different religions were not opposed to each other but joined together in God's plan. In Charlot's interpretation of The Flight into Egypt—the Holy Family flees Herod who is killing infant boys—he depicted old gods like the Nile welcoming the Holy Family as honored guests.[15] Charlot wrote:

Perhaps my special interest in the theme has to do with the relationship between pagans and Christians, the Holy Family forced to flee from their own race and country being hospitably received by pagans in a country most famed for its many 'idols'. (Jean Charlot 1976)

Flight into Egypt. 1952.

Flight into Egypt, with River Nile. 1940.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt. 1952.

In a print and three oil paintings of The Flight into Egypt, Charlot depicted the Holy Family moving from the left towards an Egyptian pyramid on the right and usually at the top of the image.[16] The pyramid represents the impressive local culture to which the Holy Family is fleeing for safety.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt with Sphinx. 1943.

Flight into Egypt. 1975.

Flight into Egypt. 1976.

Similarly, at the top right of his fresco, Charlot painted the islands' largest volcano, Mauna Loa, as a massive, pointed pyramid. The mountain actually has a rounded top and cannot be seen from the ranch, so Charlot was making a point. A clue to that point is that Mauna Loa on the right balances the chapel on the left. They are both places of worship. For Charlot, the Holy Family has been made welcome in Hawaiʻi as it was in Egypt. From above the clouds, the mountain extends its smooth slopes down to embrace the Holy Family on the left and the vaquero culture on the right.[17]

In Hawaiʻi, Charlot emphasizes, Christianity did not arrive in a religious vacuum. The seed of Christianity was not thrown on barren ground. As one Asian Christian criticized Western missionaries, "Christianity is a seed, and you brought it to us as a potted plant." The fertile ground in which a local Christianity can grow is the newly encountered religious culture with its unique history, experience, and world views. The old religion and the new interact and influence each other, developing enriched forms of Christianity that realize its infinite potential. In the fresco, Charlot depicts that interaction as a play of lines and forms. The mountain's shape is echoed throughout, for instance, in Mary's hood and her hands in prayer. The left slope is set at the same angle as Mary's head-covering. The folds of Joseph's cloak resemble the eroded mountain sides in the background.[18]

Charlot's view of religious interaction was paralleled by his activity as an artist. He had moved from France, to Mexico, to the continental United States, and finally to Hawaiʻi. In each place, he encountered new kinds of art that he needed to absorb if his own was to speak effectively to the local people (John Charlot 1976). He synthesized a new esthetic as he was broadening his religious thinking. The two activities were really one, inspired by a sense of awe before the universe and an understanding of its beauty as a unity of intimately interconnected parts. He found similar holistic visions in the religions of the Aztecs and the Hawaiians. One reason for that similarity was that their religions were developed and articulated by poets and artists. Charlot used to say that all real artists thought alike. They prayed alike as well. Daniel Dever, Charlot's confessor, described his paintings as "prayers on a wall." The images Charlot created had the power of attraction of the beauty they depicted: "Go with Helen, Louise, Zohmah to sit before picture. Also cowboys."[19]

On leaving the ranch, Charlot and his family were driven to Kīlauea where he had his first close look at the volcano:

- August 29

Leave 9:00 AM. Robert driving. View three volcanoes. lava flows: AA // PAHOEHOE.[20] Arrived Volcano House twelve noon. Log house. Hale lehua? forest.

- August 30

Walks: smoke holes, craters, lava tubes. magnifique.

The impression would inspire Charlot to create a whole new set of subjects in literature and the visual arts. At the end of his life in 1979, he turned over in his mind a design for a large vertical mural that would express his final vision of the volcano. Given instead the horizontal wall of the LCC theater, he bathed the upper part in a volcanic glow.

I thank Bronwen Solyom, Ellen Chapman, and Monty Richards for their help with information.

Charlot, Jean, 1911−1979. Checklist of Paintings. Unpublished, The Jean Charlot Collection.

——1976. "Flight into Egypt". Edited transcription. The Jean Charlot Foundation (jeancharlot.org).

^reference

Charlot, John, 1976. "Jean Charlot and Local Cultures", Ethel Moore (ed.): Jean Charlot, Paintings, Drawings, and Prints. Georgia Museum of Art Bulletin, The University of Georgia, Volume 2, Number 2, Fall, pp. 26–35.

^reference

——2005. Classical Hawaiian Education: Generations of Hawaiian Culture; Moses Kuaea Nâkuina: Hawaiian Novelist; and Approaches to the Academic Study of Hawaiian Literature and Culture. The Pacific Institute, Brigham Young University−Hawaiʻi Campus, Lāʻie, Hawaiʻi, 2005. CD-ROM.

^reference

Elbert, Samuel H., and Noelani Mahoe (eds.), 1970. Nā Mele o Hawaiʻi Nei: 101 Hawaiian Songs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

^reference-1, ^reference-2

Melrose, Maile, 1998. "Kahua Ranch: A Historical Perspective". The Waimea Gazette (waimeagazette.com), May.

^reference-1, ^reference-2

——1999. "A Poignant Painting in a Quiet Kahua Chapel". The Waimea Gazette, December, pp. 10 f.

^reference

Morse, Peter, 1976. Jean Charlot's Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii and The Jean Charlot Foundation.

Parish, Helen Rand, 1955. Our Lady of Guadalupe. New York: Viking Press.

Pukui, Mary Kawena, 1983. ʻŌlelo Noʻeau, Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 71. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press.

^reference

Saville, Jennifer, 2012. "Off in the Far Away: Georgia O'Keeffe's Letters Home from Hawaiʻi". The Hawaiian Journal of History, Volume 46, pp. 83−137.

^reference-1, ^reference-2, ^reference-3

Solyom, Bronwen, 2005. Notes on Nativity at the Ranch. Unpublished, The Jean Charlot Collection.

^reference

Nativity at the Ranch. Fresco, 4 ft × 5 ft, August 26–27, 1953. Chapel at Kahuā Ranch, Kohala, Kamuela, Hawaiʻi.

Charlot's diary records the progress of the work:

- 1953 August 19

w[ith] carpenter commencé [began] put up panel pour [for] fresco

- August 20

w[ith] Jim : 'frame' canec for fresco. sketches for cowboy and haw. cowboy. John IUKEPA [sic].

- August 21

lay scratch coat. sketches : Butch // bull. continué [continued] cartoon : fini [finished] left half.

- August 22

continué [continued] cartoon matin : sketch calf 2 weeks old Robert holds him — he fights…sketch calf 2 day old. gentil. commencé portrait v. Holt. from photos and hearsay. difficile [difficult].

- August 23

continué [continued] cartoon : v. Holt. new calf and Butch.

- August 24

trace day's task before brkfst [breakfast]. w[ith] Jim = mortar = put w[ith] float, no trowel.

- August 25

fini [finished] cartoon. trace.

- August 26

Jim plasters. paint to 6h 30.

- August 27

Jim paints white moulding around mural. dessiné [drew] candlesticks for him to make.

- August 28

PM : lime touch head Butch.

I will repeat some of these references below.

^referenceNo money exchanged hands for the commission, but our family was given the wonderful experience of ranch life—riding horses and watching cow herding and the slaughtering of a steer for the weekly meat.

^referenceCharlot's diary is written in code and several languages. The quotations in this article are my regularizations of the text.

^referenceCharlot's diary:

- August 19

Rough drive in the afternoon. Jeep. High wind.

- August 20

with children and Nesta: ride

- August 23

to fishing pond

- August 25

With Atherton, Ralley [sic: Rally], and the boys, jeep ride fern forest.

- August 27

Afternoon: children go riding with Pat.

- August 28

morning: ride: family with Pat to ginger pool: red water from ferns. Wailele… Johnny, Martin, Ann on the other ride with Pat.

[We children rode horses more than jeeps.]

The people mentioned are Nesta Obermer, friend of both the Charlots and the Richards. She donated anonymously the money for Charlot's second fresco mural in Bachman Hall: Commencement, 10 ft × 36 ft, September 12–November 26, 1953. Ralley [sic: Rally] Greenwell, assistant ranch manager. Pat Greenwell, Rally's wife. Robert remains unidentified.

^referenceProud: Pukui 1983: numbers 1813, 1988, 2276. Warriors: numbers 875, 1171, 1815, 1973. Women: number 2365.

^referenceCharlot's diary records problems with the equally symbolic calf:

- August 22

Morning: sketch calf, two weeks hold. Robert holds him—he fights. Afternoon: sketch calf two day old. Nice.

- August 23

New calf and Butch.

Butch or Butchie was the son of Ida Lincoln, mentioned below.

^referencePerhaps in Melrose 1998.

^referenceInformation for this section is from Melrose 1999: 11, and Solyom 2005.

^referenceCharlot's diary:

- August 20

Sketches for cowboy and Hawaiian cowboy.

Kale Langlas provided the information on Iokepa's home.

^referenceLincoln must have been handy, because the task was new to him and difficult in itself.

Charlot's diary:

^reference

- August 19

With carpenter, began to put up the panel for the fresco.

- August 20

With Jim: "frame" canec for fresco.

- August 24

With Jim = mortar = put with float, no trowel.

- August 27

Jim paints white molding around mural. Drew candlesticks for him to make.

Charlot's diary:

- August 26

- Give Jim drawing of church, and to Robert, drawing of calf.

Charlot also gave encouragement and advice to a teen-age ranch hand who was making drawings in a sketchbook. On returning some years later, Charlot asked to see the young man and was disappointed to find he had stopped his artwork.

^referenceBritish navy captain George Vancouver (1757−1798) brought cattle to contribute to the economic development of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

^referenceJean Charlot: Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Four Apparitions, 1959, fresco, 12 ft wide × 9 3/4 ft high, St. Benedict's Abbey, Atchison, Kansas. Photograph: Glenda Carne.

Jean Charlot: Illustration of Helen Rand Parish: Our Lady of Guadalupe, Viking Press, New York, 1955. Photograph: Glenda Carne.

Jean Charlot: Madonna and Child, 1959, ceramic statue, 5 ft high, St Francis Hospital, Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. Photograph: Philip Spalding III.

Jean Charlot: Mary our Mother, 1978−1979, ceramic statue, 15 ft high, Maryknoll Grade School, Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. Photograph: Philip Spalding III.

^referenceThe original image is the figure itself. All the gold, the sunburst, the stars on the cloak, the moon, and the angel were added later.

^referenceJean Charlot: Flight into Egypt, 1952, lithograph, Morse number 557. Flight into Egypt, with River Nile, oil, 1940, Checklist 633.

^referenceCharlot: Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1952, lithograph, Morse number 536. Jean Charlot's Checklist of oil paintings numbers 633 (Flight into Egypt, with River Nile, 1940), 704 (Rest on the Flight into Egypt with Sphinx, 1943), 1342 (Flight into Egypt, 1975), 1347 (Flight into Egypt, 1976).

^referenceThis passage in the fresco might be influenced by the view of Haleakalā sometimes available on driving to the ranch. The summit of that volcano is not, however, pyramidal. The clouds also indicate to the viewer that the geometric shape Charlot gave Mauna Loa is not a man-made pyramid.

^referenceI thank Joseph Stanton for this point.

^referenceDiary August 27. Helen Richards, Louise Judd, Zohmah Charlot.

^referenceTwo types of lava.

^referenceContact, copyright, credit

Jean Charlot

&

The

Jean Charlot Foundation