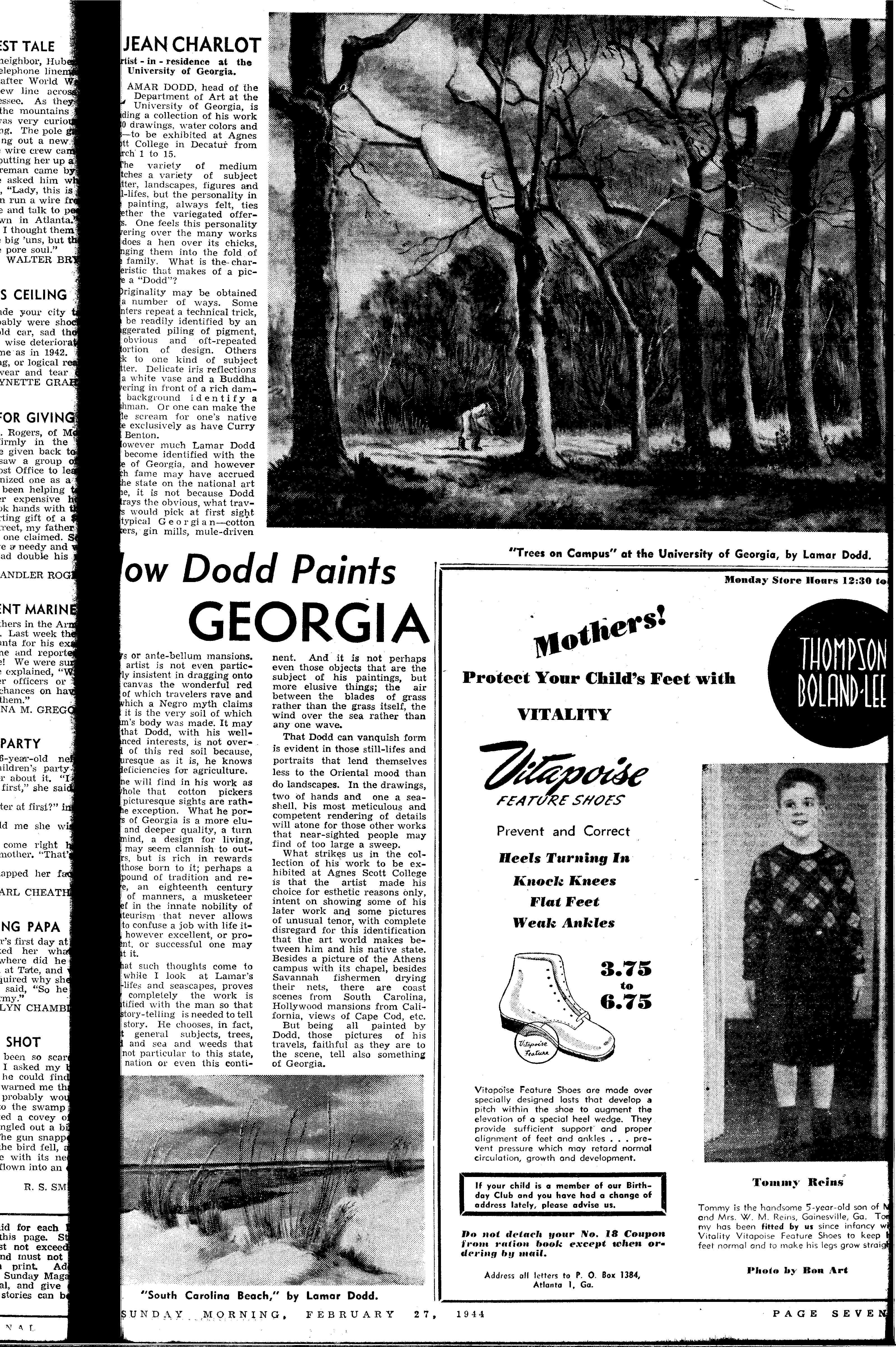

How Dodd Paints GEORGIA[i]

By JEAN CHARLOT

Artist-in-residence at the University of Georgia

Lamar

Dodd, head of the Department of Art at the University of Georgia, is sending a

collection of his work—30 drawings, water colors

and oils—to be exhibited at Agnes Scott College in Decatur from March 1

to 15.

The

variety of medium matches a variety of subject matter, landscapes, figures and

still-lifes, but the personality in the painting, always felt, ties together

the variegated offerings. One feels

this personality hovering over the many works as does

a hen over its chicks, bringing them into the fold of one family. What is the characteristic that makes of

a picture a “Dodd”?

Originality

may be obtained in a number of ways.

Some painters repeat a technical trick, can be

readily identified by an exaggerated piling of pigment, an obvious and

oft-repeated distortion of design.

Others stick to one kind of subject matter. Delicate iris reflections on a white

vase and a Buddha hovering in front of a rich damask background identify a

Pushman. Or one can make the eagle

scream for one’s native state exclusively as have Curry and Benton.

However

much Lamar Dodd has become identified with the state of Georgia, and however

much fame may have accrued to the state on the national art scene, it is not

because Dodd portrays the obvious, what travelers would pick at first sight as

typical Georgian—cotton pickers, gin mills, mule-driven drays or

ante-bellum mansions. The artist is

not even particularly insistent in dragging onto his canvas the wonderful red

soil of which travelers rave and of which a Negro myth claims that it is the

very soil of which Adam’s body was made.

It may be that Dodd, with his well-balanced interests, is not over-fond

of this red soil because, picturesque as it is, he knows its deficiencies for

agriculture.

One

will find in his work as a whole that cotton pickers and picturesque sights are

rather the exception. What he

portrays of Georgia is a more elusive and deeper quality, a turn of mind, a

design for living, that may seem clannish to outsiders, but is rich in rewards

for those born to it; perhaps a compound of tradition and reserve, an

eighteenth century cast of manners, a musketeer belief in the innate nobility of

amateurism that never allows one to confuse a job with life itself, however

excellent, or proficient, or successful one may be at it.

That

such thoughts come to me while I look at Lamar’s still-lifes and seascapes, proves how completely the work is identified with

the man so that no story-telling is needed to tell this story. He chooses, in fact, most general

subjects, trees, sand and sea and weeds that are not particular to this state,

this nation or even this continent.

And it is not perhaps even those objects that are the subject of his

paintings, but more elusive things; the air between the blades of grass rather

than the grass itself, the wind over the sea rather than any one wave.

That

Dodd can vanquish form is evident in those still-lifes and portraits that lend

themselves less to the Oriental mood than do landscapes. In the drawings, two of hands and one a

seashell, his most meticulous and competent rendering of details will atone for

those other works that near-sighted people may find of too large a sweep.

What

strikes us in the collection of his work to be exhibited at Agnes Scott College

is that the artist made his choice for esthetic reasons only, intent on showing

some of his later work and some pictures of unusual tenor, with complete disregard

for this identification that the art world makes between him and his native

state. Besides a picture of the

Athens campus with its chapel, besides Savannah fishermen drying their nets,

there are coast scenes from South Carolina, Hollywood mansions from California,

views of Cape Cod, etc.

But

being all painted by Dodd, those pictures of his travels, faithful as they are

to the scene, tell also something of Georgia.